We are incredibly lucky to have what is the most complete set of Cistercian ruins in Britain right here on our doorstep. To the people of Leeds, Kirkstall Abbey is a part of their everyday landscape. Many pass it daily on their commute to and from work, and it is a popular choice for families wanting a scenic walk and picnic in the warmer months.

But just how much do we know about Kirkstall Abbey? When was it built, and by whom? What was life like at the Abbey? This month we delve into the history of this magnificent structure and look at how it has been used throughout the centuries to present day.

The Beginning

In 1147 a community of twelve monks from Fountains Abbey set up a daughter-house at Barnoldswick. This land was granted to them by Henry de Lacy, who at a time when he fell seriously ill had promised to found a religious house should he recover. The monk’s time in Barnoldswick was not an uneventful one. Upon arrival, they found an already established parish church where locals worshipped each Sunday and feast days. The monks wished to live in solitude and this interfered with that desire, so the abbot tore down the church! This of course provoked outrage among the locals and the pope had to intervene with court proceedings to save their skin. The chronicler of the house at the time wrote, ‘no small controversy arose concerning such an unusual and highhanded proceeding.’ While, thanks to the pope, the court found in the monk’s favour as it was reasoned that for a church to fall and an abbey to rise was a pious act, the locals never forgave the Cistercians and did not welcomed them into the neighbourhood. Another problem with the site at Barnoldswick was that it became evident that it was not Henry’s land to give away, as he rented it from the Earl of Norfolk and had neglected to pay the agreed terms of five marks and a hawk per annum for several years. An extreme spell of wet weather also ruined the monk’s crops and Abbot Alexander contemplated a change of site following the six years of hardship.

Back in the 12th century, Kirkstall was a secluded, wooded area in the valley of the River Aire, and during travel through the area, Alexander thought this might be a perfect spot for relocation. At this time the locality was inhabited by several hermits and the land belonged to William Peitevin who held it of Henry de Lacy. The Foundation of Kirkstall says it was ‘A place covered with woods and unproductive of crops, a place destitute of good things save timber and stone and a pleasant valley with the water of a river which flowed down its centre.’ Abbot Alexander approached de Lacy about the possibility of relocating, and he was apparently the driving force behind William’s grant of the land, woodland and water to the monks. The group relocated to Kirkstall in 1152. The site was ideal for setting up the new community with the River Aire being used to transport stone from the quarry, Hawksnorth wood provided shelter, fuel, pasturage and building resources and a water supply was channelled from springs and streams that ran above the abbey. Several of the hermits living in Kirkstall joined the community. Abbot Alexander’s 35 years in charge saw the essential building work completed at Kirkstall.

By the end of the 12th century, the church, the monks’ and lay-brothers dormitories and refectories, chapter-house and cloister along with other necessary buildings within the abbey were all completed in wood and Bramley Fall stone, and roofed with fine fired clay tiles and ‘thackstones’. Henry de Lacy himself laid some foundation stones in the church with the monks and lay-brothers labouring together to build the structures. Skilled stone masons were brought in to do the carving. This building work was incredibly expensive, and in 1186 Kirkstall was one of the eight Yorkshire houses that owed Aaron, the Jew of Lincoln, a combined sum of 6400 marks. It is hard to put a comparative on this figure in today’s money, but it is almost certainly well into six figures!

Kirkstall Abbey continued to develop and prosper into the 13th century, gaining grants of land, money and other goods.

The Life of a Cistercian Monk

Life as a Cistercian Monk was renowned for its severity. Observing ideals of poverty and simplicity they wore simple habits of undyed wool, and only wore breeches when travelling. They were regularly known as the ‘White Monks’ due to the undyed grey-white of their habit. At this time dyes were expensive and was therefore a luxury. Turgisius, the fourth abbot of Kirkstall was known for his strict discipline. In winter, the monks were allowed to wear two layers of clothing but Turgisius wore only the bear minimum of clothing and no footwear. He was said to seem unaffected by the cold while the other monks stood freezing in their layers. The Cistercians were also renowned for refusing to wear trousers, following literally the rule of St Benedict. An amusing anecdote by Walter Map c. 1181-93 goes as follows “The lord king, Henry II, of late was riding as usual at the head of all the great concourse of his knights and clerks…There was a high wind; and lo! A white monk was making his way on foot along the street and looked around, and made haste to get out of the way. He dashed his foot against a stone and…. fell in front of the feet of the king’s horse, and the wind blew his habit right over his neck so that the poor man was candidly exposed to the unwilling eyes of the lord king.” Map ends his recount by adding “Still, the monk who tumbled down would have got up again with more dignity had he had his breeches on.”

Their diet was frugal, with meat forbidden and seasonings such as pepper and cumin were considered a luxury to be avoided. The monks ate only once a day, except in summer when a light supper was also served to sustain them during the longer daylight hours. A typical meal was coarse bread with vegetables, herbs and beans. On feast days and anniversaries, they were served pittances – which could be fish, eggs and other delicacies. Ale or wine was drunk but was also restricted in amount.

Manual labour was an integral part of life to the Cistercians and they would spend a part of each day working, also joining the lay-brothers in the fields at harvest. They saw this manual labour not only as a means to be a self-sufficient community, but also to practice humility. This devotion to work was admired by many, but not all. Benedictine abbot of Cluny, Peter the Venerable said “It is unbecoming that monks, the fine linen of the sanctuary, should be begrimed in dirt and bent down with rustic labours.” The other two thirds of a monk’s day would involve worship and divine reading.

Over the Years

The community at Kirkstall Abbey faced ups and downs over the years, there were times of financial hardship and the loss of lands. As one of the major landholders in the country though, the abbot of Kirkstall was called upon to help deal with church matters. In 1311 he was summoned, amongst others, to suppress the Knights Templar. The abbey was one of the Yorkshire houses to provide a home to a former Templar who had been absolved. The following year it was reported that the Templar had been allowed to escape!

Kirkstall was also affected by the Black Death. It is unknown just how many died of the plague but records suggest the disease took its toll on them. During 1348-55 there was a quick succession of four abbots, and by 1381 there were only sixteen monks and six lay-brothers remaining.

Other problems occasionally faced by the community was unbelievably criminal accusations, and records show that behaviour at Kirkstall was not always pious! In 1356 it was alleged that the abbot of Kirkstall led five monks and a lay-brother to besiege Thomas Sergeant’s house in Thorpe near Knaresborough. Apparently they damaged the house, stole his possessions and imprisoned him at Wetherby. The reason for this act is not evident.

Apart from this and other infrequent misdemeanours, life continued at Kirkstall relatively peacefully until Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the monasteries. During 1535-36 Doctors Layton and Legh were commissioned to visit 121 religious houses in the north to compile a report on religious life in the area. They gained an unpleasant reputation during their tour for rigorous questioning and their rude manner. Their report on Kirkstall listed three cases of sodomy, veneration of an object purported to be the girdle of St Bernard and an income of £329 per annum. These findings were read out in Parliament along with other reports as evidence of the poor state of religious life, thus paving the way for the first phase of the dissolution. Kirkstall avoided this first stage but eventually had to surrender in November 1539.

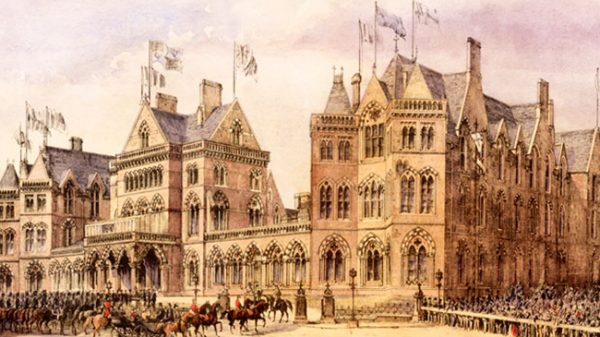

Following the surrender, the buildings were stripped of lead, gutters and water pipes were removed and melted down and the furnishings and roof timbers were stripped out. Other than that, the abbey escaped relatively unscathed with many of the buildings left standing to use for agricultural purposes. The stone was not plundered at the time, but disappeared more slowly over the years. It is said that the steps leading to Leeds Bridge are made from the abbey’s stone. Also, neglect and weather conditions caused the further decay of the building and in 1746 the western range fell. Strangely, the people of the 18th and 19th centuries saw fit to take the main thoroughfare to Leeds right through the nave of the church, causing the destruction of the east window! The road was finally redirected in 1827.

Kirkstall Abbey in Recent Times

Kirkstall Abbey is now a wonderful place for people to visit. Open to the public, it makes for an enjoyable and educational outing whether you go to soak up the history of the monument or simply take in the scenic riverside setting. It is also used for many events and has been the set for television productions such as the BBC’s Frankenstein. Intimate theatrical performances, big movie screenings and classical concerts are also held there such as Classical Fantasia which was a highly popular annual event until it was cancelled last year. The Kirkstall Festival a yearly event will be there in July. Run entirely by Leeds volunteers, it attracts thousands of people with stalls, fairgrounds, food & drink and much more. Massive stars such as Leeds’ own Keiser Chiefs have played concerts at the abbey too.

Another popular event held regularly at Kirkstall is the Deli Market. Held on the last weekend of the month from 12 noon – 3pm between March and November, there are over 40 stalls packed with food such as speciality cheeses, meats and delicious cakes and treats, hand-made crafts, jewellery and other items from local Yorkshire producers.

In the old gatehouse of the abbey, is the Abbey House Museum. This is a fantastic museum for children and adults alike. You can step back in time to wander through a Victorian street and there is a vast array of toys through the years to look at. It is a highly interactive museum and there are always lots of activities for children to get involved in. It hosts many exhibitions throughout the year on an array of subjects, one such exhibition celebrating the centenary of the girlguiding senior section is on now, for more details see our article on page 19.

Kirkstall Abbey is certainly a jewel in the crown of Leeds. We are truly blessed to have such a wonderful building on our doorstep that is so rich in history, far more than we could include here. If you have not had the opportunity to visit the abbey before, it is highly recommended!